The images and stories in this RTA portraying my life journey with cancer are entitled:

Origins

My Family, My Culture

Rag Doll

The Demon Within

The Silent Scream

The Fighter

Feather Inscape

Slipping Away

Living Horror

Mother

Morphine

Heart of Peace

Living in the Shadows

Cancer (Mis)information

Withdrawing / Emerging

Origins

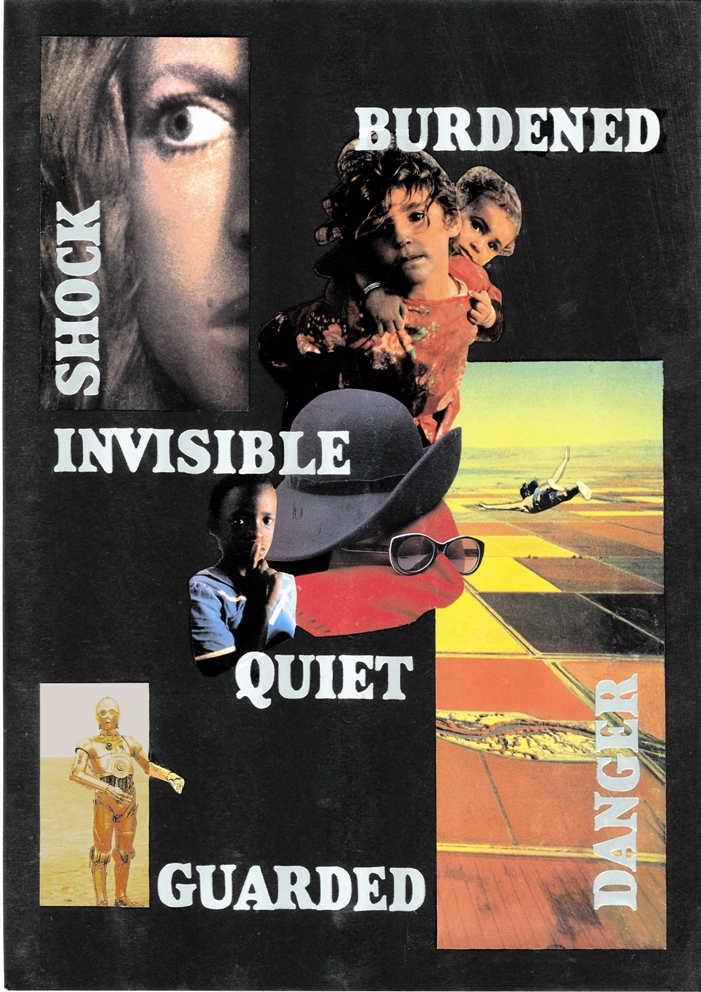

OriginsThis collage represents my way of being in the world when I was a child, a way of being that was inextricably related to my environment. My parents had migrated with their children from Malta (islands with an ancient and mixed cultural heritage, located in the heart of the Mediterranean). My mother’s was a traditional role inherited by women of her generation and persuasion: one of bearing one child after another, and of being forever tied to house and family. In Malta, she lived in a patriarchal society with strong Catholic beliefs and strong family loyalties, which served to embed her in her oppressed way of life, tying her ever more tightly to her society’s culture and values.

She had given birth to thirteen children. Her workload was such that she could only attend to our very basic needs. She was constantly cooking, cleaning and sewing from morning till night, day after day, year after year. My father’s role in the family was shaped and conditioned equally by the patriarchal culture in which he lived. His career and identity was military; he was, in fact, a gunner in the Second World War. I expect that he endured the loss and suffering of family, friends and allies in the aftermath of the heavy bombardments the Maltese islands sustained (in fact, the most heavy in the world) – an experience, I believe, that both traumatised and brutalised him. His decision to migrate to Australia with the family came from his loss of job prospects some years after the war. He was also concerned about his children’s limited prospects in Malta and about keeping the family together.

In retrospect, I believe that the migration experience – which tore me away from the relatives I cherished, and a place and culture that were familiar to me – had much to do with the anxiety I felt when I was young. I turned four years old when we arrived in Australia. Another important factor was the dynamics that played out within my family of origin. I suspect that the war had a way of infiltrating the family experience. Under stress, there were feelings of rage (expressed and unexpressed), blame and powerlessness. My siblings’ response to this treatment was unordered, sometimes unpredictable and confusing. Some (like myself) stayed on. Some ran away, and some disappeared. I sometimes did not see missing sisters or brothers for years after they left home. I was the second youngest, the twelfth child in this family. I stayed at home, because my mother became critically ill when I was 13 and I felt an obligation towards her, and because I had nowhere else to go.

As a younger introverted child, I hated the violence. I felt deeply troubled, but powerless to change my family’s circumstances. At the same time, I so wanted the pain to end. The emotions identified in this collage are shock, guardedness, feelings of danger and of being burdened (with problems not of my own making). Being quiet and invisible were coping strategies I employed to survive what then seemed a chaotic and dangerous environment. I hoped that if I did not draw attention to myself, then I would not be targeted for abuse or punishment. The picture of the skydiver expresses a death wish. In my child’s mind, death by suicide or by accident seemed an appropriate way out. I never acted intentionally on this desire and no-one ever knew.

My Family, My Culture

My Family, My Culture

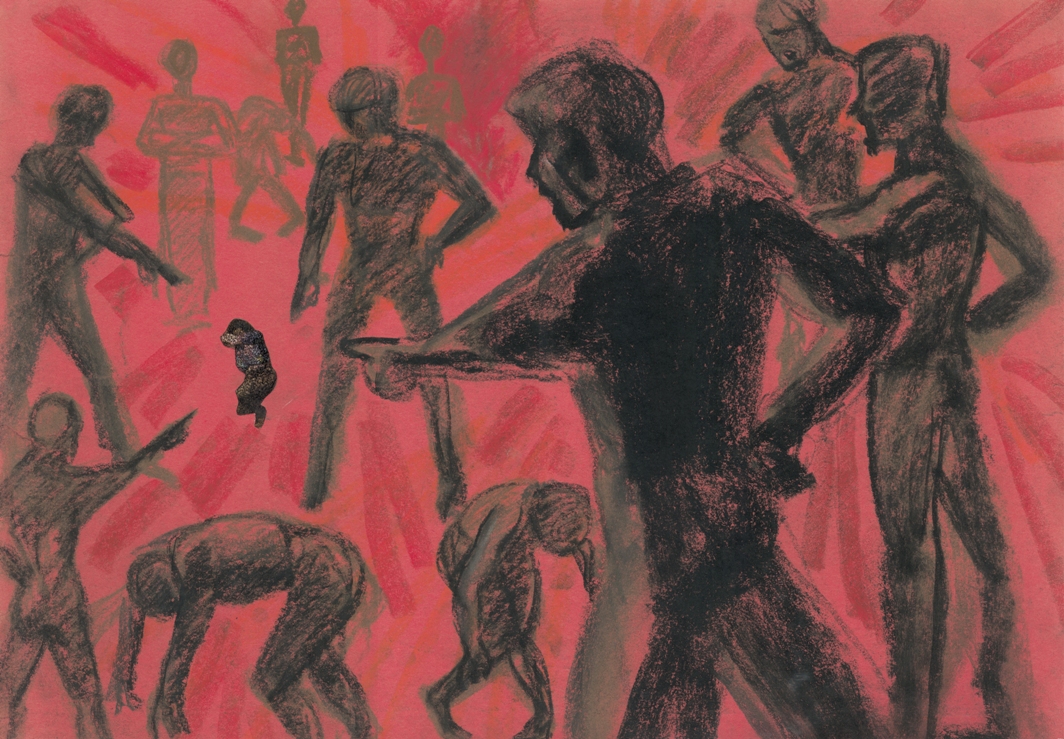

The Satir Communication Stances inspired this drawing. Family therapist, Virginia Satir, described the five main stances people take when stressed or under pressure: the blaming, placating, super-reasonable, irrelevant or congruent stances. My family of origin and the Australian culture I grew up in were both patriarchies. As such, masculinity and masculine values and characteristics were idealised. My experience of being female in the culture of patriarchy was primarily one of victimisation. Consequently, in this illustration, I am represented by the small crouched figure. This is a visual representation of the “placating” response.

The illustration of my cowering self is actually a photo. I took on the placating position physically, as described by Virginia Satir, one of fending off physical and psychological attacks. I coloured myself black, because I am undisputedly a part of this culture, albeit the part that is regarded as bad, threatening, untrustworthy, inferior and weak. I drew this originally to represent my place in my family of origin. More recently, I have come to perceive this as equally representing my encounter with certain aspects of the medical profession. For example, together with medical terminology, there is in scientific and medical literature, language drawn from military concepts and jargon. A leading cancer researcher likened the present treatment of cancer to “throwing a hand grenade at it and hope it kills more bad cells than good”. To pose a question: How different could medical treatment be, if instead of “blasting” the cancer, using “slash and burn” techniques, “fighting” and “killing off” cancer cells, “winning” or “losing the battle”, a very different conceptual model is used?

In the drawing there are figures doubled over. This posture represents the “irrelevant” stance. I associate the “irrelevant” stance with how I was feeling internally at the time I approached the medical profession for help. It was a feeling of collapse, of being drained of energy. This was my initial experience of cancer. Yet, it was at this time, while I was feeling in a state of collapse and shock, that I was required to make important life and death decisions – urgently – about treatments. I knew better than to obey instructions blindly and to follow recommendations without question. I’d seen my mother and two adult sisters through their ordeals with cancer. Only my mother survived. I also knew better than to make the unconscious deals I’d seen others make, the tacit bargains made out of desperation and sheer terror by cancer patients with their doctors: “If I praise you and do everything you say, would you please, please make sure I don’t die. Would you please save me?” The doubled over stance then becomes one of mock reverence.

I had well-researched reservations about some treatments and refused them. My refusals were not well received generally. I finally found myself being labelled “a difficult patient”. This seemed to give medical staff permission to treat me with disregard and condescension. It is now clear to me why many cancer patients hand over their power readily: the (seeming) urgency of the situation, with little or no time to really think things through, the desperation and powerlessness one feels, and the very human (and Christian) inclination to look for a saviour. The sad truth is that some doctors too readily accept the power given them, when they cannot deliver honestly on their promise.

Rag Doll

Rag DollThis is an old drawing, which was rendered in response to an Art Therapy class assignment on childhood transitional objects. We were asked to draw our favourite childhood toy. I drew a rag doll in crayon with my non-preferred, left hand, so as to facilitate childhood expression. It is an imaginary doll I would have liked. I drew the image on black paper, without much thought. My memory of that time was mostly of feelings of sadness, aloneness and fearfulness. In a word-association exercise, I wrote variations of the description “limp”. I associate the word and image with the powerless I felt at the time. Also, a rag doll offers no resistance. As a child, I very often did not realise how much distress I was feeling. In retrospect, I believe this was because I had become accustomed to that way of being; it had become normal and natural to me.

I recreated inadvertently this highly anxious state in my work of choice and lifestyle later on in life. For instance, therapeutic work with people with drug addiction and domestic violence problems – while doing my Masters degree – seemed satisfying and worthwhile endeavours. At the same time, this overload proved detrimental to my health. One of the health problems I finally had was burn-out. By being present emotionally when engaging with disturbed clients, I suffered energetic contamination or depletion. I did not realise fully this risk to my health over a long period of time. Consequently, I did not provide myself with the self-care strategies that could have offset damage to my health and well-being.

I clearly had a pattern of being locked into situations, which were highly stressful. I am aware that while I was unable to escape my family environment, as an adult, I could have escaped a stressful work situation and an overwhelming workload. The point is that at that time I did not recognise my workload as being highly stressful and personally damaging. I believed truly that hard work was very appropriate, very necessary, and very worthwhile, and that all my efforts would enable me ultimately to transcend my childhood legacy. I thought that if I finally landed on the “right side of the desk” as a counsellor, it was proof that I had succeeded in transcending my childhood patterns. On reflection, I was wrong. I did not realise that I was repeating a dangerous pattern of unconscious self-destruction.

In this drawing, I associate the doll’s attractiveness and open arms with my childhood need for affection and acceptance. The most distinct facial features are the large eyes and the relatively small mouth. I associate the wide open eyes with shock and fearfulness, also with vigilance and alertness. The small mouth indicates the reticence I felt. As I look at this image of an open-armed, wide-eyed, child-like figure with a torn and tattered dress, it seems a fitting symbol of my former childhood self in a distant, almost-forgotten past.

The Demon Within(two images)

The Demon WithinThese two illustrations are old images taken from a dream. This is an example of what I call a “healing dream”.

At the time I had this dream I was struggling with a situation I did not know how to resolve and it had been disturbing me for months. I had been humiliated and rejected by someone, who was important to me and I did not respond. At that point in my life, this was my usual way of dealing with this kind of interpersonal difficulty. I would feel ashamed, then I would remove myself from the “blamer’s” life altogether. The abuse was not deserved. Nevertheless, I tended to feel a sense of responsibility and would agonise about how I could redeem the relationship.

When I reflect on this, I can clearly see how my response – or lack of it – came about and how it became reinforced. As a child it was too dangerous for me to react to the abuse at home. To defend oneself, or to react with anger or rebellion, seemed to escalate the rage being expressed. (My actual response was to scream, a response that did not fit into any of these categories. The interesting thing was that it was at times effective, as the violence would stop.) The tendency to feel guilty, I believe, also comes from my childhood when it was necessary – or required of me – to take the blame. The need and desire for the difficulty to be resolved and for the relationship to remain intact is also understandable in the context of my childhood longing for peace, love and security. Understanding the childhood connection is, of course, not enough. Understanding alone does not offer a solution, that is, a way in which this recurring pattern in my life might be resolved skilfully. The solution came to me in this dream. It provided me with insights that helped me to put a stop to this habitual response.

The dream came two nights after I attended a weekend workshop with three skilled facilitators, two of whom were transpersonal psychologists. It was a weekend full of creative expression; we danced, played, created art, myths and stories. In the dream, I was with a group of people in an old castle, among trees, on a mountainside. We were tossing around ideas about the afternoon’s activities. Someone suggested horse riding. My immediate reaction was to dismiss the idea – I thought it too macho; in any case, I did not know how to ride a horse. Then, I noticed a strong, capable looking woman, an androgynous type, sitting on the floor with legs straight out and leaning comfortably against the wall. Inspired by her air of confidence, I found myself reconsidering my stance – perhaps I could learn to ride a horse. (This, I think, represents an invitation to learn to be skilful instead of going with my “natural” inclination.) Suddenly an announcement was made: the devil was coming and he was due at any time now. A silence fell on everyone in the room. They quietly went into a larger adjacent room and formed a large circle, several rows deep. The room darkened, the atmosphere was very intense, the mood sombre. We were waiting in suspense for this awesome power to arrive.

During this time I found myself wondering how best to deal with this situation. I wanted to make the most of this encounter. Then, suddenly, the huge castle door creaked slowly open. The devil came vaguely into view. I thought I saw a skeletal figure in a blur of orange and white against blackness. When he came in people crowded around him. I could barely believe what I saw; I circled the crowd to get a closer look. It was the figure of a mendicant, stooped and humble. He was going around the circle to each person asking, begging their forgiveness. It occurred to me that he looked very much like the abbot of a Buddhist monastery and lay community centre where I once stayed. I decided I definitely wanted a personal encounter, so I made my way through the crowd towards him. He finally looked straight at me. Nothing had changed. Without moving his eyes, he spoke to me with great awareness, and great presence. He was anxious and repentant. He said: “I am very sorry. Please forgive me.” Suddenly, I saw in front of me all the significant men in my life, with whom I had experienced hostile or conflicting encounters and with whom I was left feeling humiliated and worthless. All were now in my presence asking, begging for my forgiveness and treating me with great respect – as if I mattered greatly to them. Being treated with genuine respect by these men was strange to me. It was a very moving and healing experience.

As I reflected upon my interactions with these various men in my life, I realised very clearly that they were men of a particular type. I came to understand that their abusive, unjust treatment of me was based on their tendency to blame others (women) for their own mistakes and personal limitations. In other words, I was – consciously or unconsciously – their scapegoat. The abbot, I knew, was inadvertently such a man. He was a monk of the Theravada Buddhist tradition, who had stated publicly that a woman is more dangerous to a monk than ten thousand tigers. This statement was presumably meant to protect a monk’s celibacy, but it is a misleading statement. It is dishonest ultimately, and harmful to women both individually and collectively. In truth, it is not women (or men), who are dangerous to celibates, because of their natural sexuality. It is the feelings of craving that arise within a person, which can be dangerous, and which should kept in check. I knew instinctively such a man was not a true ally, and yet this was an abbot, a man of authority – like my father, one I was conditioned to honour and treat with respect.

The insights I gained from this dream have enabled me to face people of this type. In their presence, instead of abjectly disappearing from view hoping to avoid abusive treatment, I now respond very differently. I no longer want to appease offensive men (or women). My intention now is to redeem myself in my own eyes, to behave with self-regard and dignity, and to act with integrity, knowing that I am not responsible or to blame for the feelings of discomfort, inadequacy or shame that arise in others.

I think this was the turning point in my behaviour towards abusive men, and in particular, those in positions of authority in this patriarchal culture – some medical (and alternative) practitioners, for example. When I now treat doctors with respect, it is not automatically given, because of their gender or their professional status. I look beyond the person’s role and appearance. I am cautious generally and I make a point of taking personal responsibility for any decision about my treatment that may be made, because I clearly know that there may be a conflict of interests. Some doctors today are not yet holistic in their knowledge and methods, and they are essentially people in business. This being the case, medical treatments are limited in their scope, and medical practitioners’ ethical conduct may be compromised.

The Silent Scream

The Silent Scream

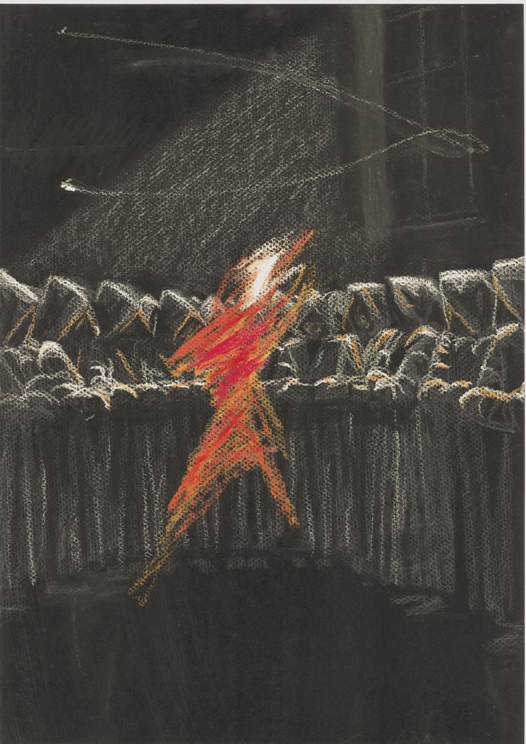

This illustration came to mind when I remembered the reality of being afflicted with metastatic cancer – a disease that had progressed to the point of imminent death. I mention in the commentary of the illustration entitled “The Fighter” that my night time experience of living with metastatic cancer was horrific. This illustration depicts the daytime reality. This is about the anguish of knowing my predicament consciously; of being aware absolutely of what is happening to my body, to my mind, and to my spirit.

Looking at the illustration, I notice that the eyes are closed. On reflection, this represents a looking inward, looking within, connecting with my inner reality, my feelings. At that time, my feelings were multi-layered. The pain related to both physical and psychological agony. I describe the pain as agony, because of the intensity of the feelings involved. In this illustration, the demeanour of the figure suggests one who is calling, in a desperate call for help. Alternatively, the mouth is open to produce a scream, but it is a scream that is not heard.

In terms of the physical suffering, there was – primarily – the ever increasing pain; the tumours were in my bones at various points and in varying sizes throughout my skeleton. There were also multiple tumours in the soft tissues, and some could be felt beneath the skin. In addition to the tumours, there was the mutilation of the body – the surgery and its consequences. I became aware that from the time of the surgery onwards I would have to worry about the reality of living – every day – with physical discomfort and the dread of disproportionate swelling, brought about by the removal of lymph glands. I had expected the “experts” to give me all the factual information, and to alert me to these potential effects. They did so in full, only after the surgery.

The psychological impact was equally distressing. The primary feelings were one of helplessness and grief: helplessness at my perceived powerlessness to do anything about this situation; and grief, inconsolable grief, over the losses I’d already experienced and over the losses I was in the process of experiencing. Losing my health and my ability to function in the world was not only unimagined by me, but also the source of great sorrow. I could not do those simple things I used to take for granted: I could no longer sit, stand, walk, or enjoy listening to music or reading. I could no longer earn my own livelihood. I’d lost my career, my life’s work, and with it the opportunity to apply the skills, which I had spent many years at University and in the workplace to cultivate.

Michael and I had left the home we had made for ourselves in the 16 years we lived in Perth, and with it some dear and cherished friends. The greatest sorrow I experienced – apart from the loss of my health – was the impending loss of my primary relationship with my husband, Michael. Our relationship of mutual support had changed dramatically to one of my dependence on him. The prospect of losing him completely, his love and his physical presence was very, very painful to me. At the same time, I witnessed Michael’s suffering, his own distress at the prospect of losing me, at the prospect of losing our relationship – the one source of true love, peace and joy in our lives.

When I look back on this time, I remember vividly seeing the pain in Michael’s eyes; the look of pain that was very hard to behold, and very hard to bear. I also remember my response; I felt responsible for his suffering. Yet, there seemed little I could do to change what was happening. Nevertheless, I made a resolve, a promise to myself, that I would do anything I could to lighten his load. Certainly, there were times I felt I could easily slip away, and there were times I truly wanted to. At those times, life had become so painful, so tragic, that death seemed a merciful release. Equally, there were times I made extra efforts to overcome the crisis I found myself in. I think this is one of love’s greatest strengths. Love inspired me to overcome my difficulties, even those difficulties that seemed impossible to overcome. There is now one thing I can say without a doubt: that love created the turning point, the motivation and path towards healing.

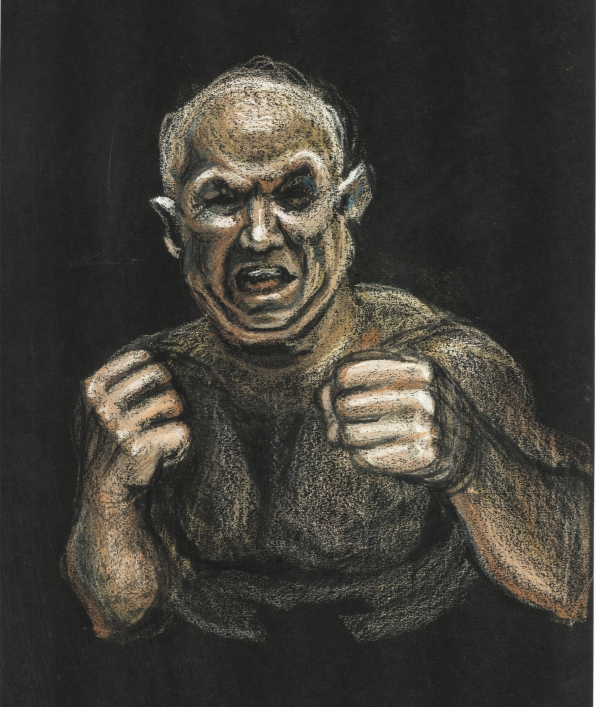

The Fighter

The FighterWhen I was on large doses of morphine (200 mg daily), my sleep was full of nightmares. In my dreams, I was shot, punched, kicked, knifed; I experienced tsunamis, landslides, earthquakes, and volcanoes erupting – the many variations of catastrophic and apocalyptic events. Night after night, these dreams would come, and I would invariably wake up in panic. That was the first time in my life that I experienced panic attacks. I would wake up with a start and shake uncontrollably. I was also weary and constantly terrified. I dreaded the prospect of living another day, of sleeping another night.

This illustration depicts a figure in one of my dreams. He was a hefty man in the process of punching me. His intention was to knock me out. His demeanour was fierce and determined. I was repulsed by him. At the time I was having these nightmares, I felt overwhelmed by what I was experiencing. My reality by night and by day was filled with horror.

These nocturnal images were accompanied by feelings of helplessness. Very often, I would wake in the middle of such dreams. I was left with clear images of unrelenting aggression in my mind, and with feelings of devastation.

As I reflect on this image, I see that it represents my experience of cancer, at that time. It was an aggressive, seemingly unstoppable form of cancer. There was a very real prospect of losing my life to it. I felt overwhelmed and overpowered by it. I perceived the cancer at that time as being far too strong, too fierce, and too aggressive to overcome. I felt my hope for a recovery was now futile. I was both terrified and horror-stricken by its destructive effects on my body, mind and spirit.

It is significant to me that I did not sense – however great the battle or struggle – that the “enemy” in my dreams was the final victor. This might suggest that in my battle between life and death, I was not altogether convinced that I would not survive. I am also aware that this image came from my body/mind/spirit. I suspect that I am looking at a mirror image of an aspect of my own self. In this sense, the creation and creator are one. “The fighter” – ultimately – is the fighter in me.

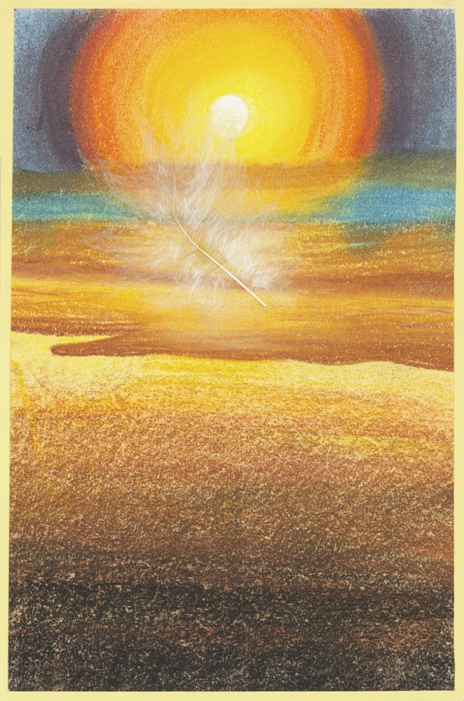

Feather Inscape

Feather InscapeThis is an old drawing. It is a landscape that still comes to mind, particularly during difficult times. This image was rendered many years ago, when I was doing a Masters degree in art therapy, following an exercise set in class. We were to use an image of a symbol of the self and to create a landscape equivalent in nature.

My symbol at the time was a feather. I chose the feather as my symbol after noticing that I frequently used feathers and associated images and themes in the art therapy journal I created. I used the feather as a symbol, which related to a bird. To me, it was a symbol of transcendence, which inspired larger vision and spirituality. My supervisor at the time said that there are other qualities that are also suggested by my symbol. He said that in my work as a therapist the symbol of a feather suggests that I could help clients find their lightness, their softness and their freedom of spirit.

On reflection, my supervisor’s comment was more significant than I then realised. I remember that, at that time while I was doing my art therapy degree at Master of Arts level, I was working professionally on an outreach, home-visit basis with women (mothers) with drug addiction and other major problems. It was also the end of semester at the University and I was in the process of finalising and handing in work for assessment. My combined workload was weighing heavily on me and I desperately needed a break. I imagined the kind of place I was drawn to for a holiday and this particular image came to mind – a place in the sun, close to the sea, in the stillness and beauty of sunset.

Coincidentally, the image that came to mind was also to me a landscape, equivalent to the symbol of a feather. The qualities of lightness, softness and a freedom of spirit, which my supervisor suggested were associated with the symbol of the feather, were the antithesis, the exact opposite, of how I was feeling personally at that time. While my supervisor framed the qualities of my symbol as those qualities I could offer as a therapist, they were also qualities I needed to develop and feel in myself. As I reflect on this, I now realise that the image of a feather so accurately symbolised what I most needed, what was missing for me at that point in time. These many years later, I can now see that this insight was the whole point of the exercise. I chose instinctively the symbol of the feather, which represented simultaneously certain qualities that I already possessed, as well other qualities that I needed to develop – my potential qualities, my limitations.

I recall that during times of great distress and difficulty in my life, this image has consistently come to mind. It is a comforting image, which engenders a sense of peacefulness, contentment and harmony. It occurs to me, as I look at this landscape more closely, that there is not only a consistency in the way I create this image in my mind during times of stress, but there is also a sense of familiarity and a significance about the image itself and the feeling of longing associated with it. Ultimately, I sense that this is not a created image, an imagining. It is more a memory. I am remembering my homeland, Malta, my birthplace – islands in the sun, being close to the sea, in the stillness and beauty of sunset.

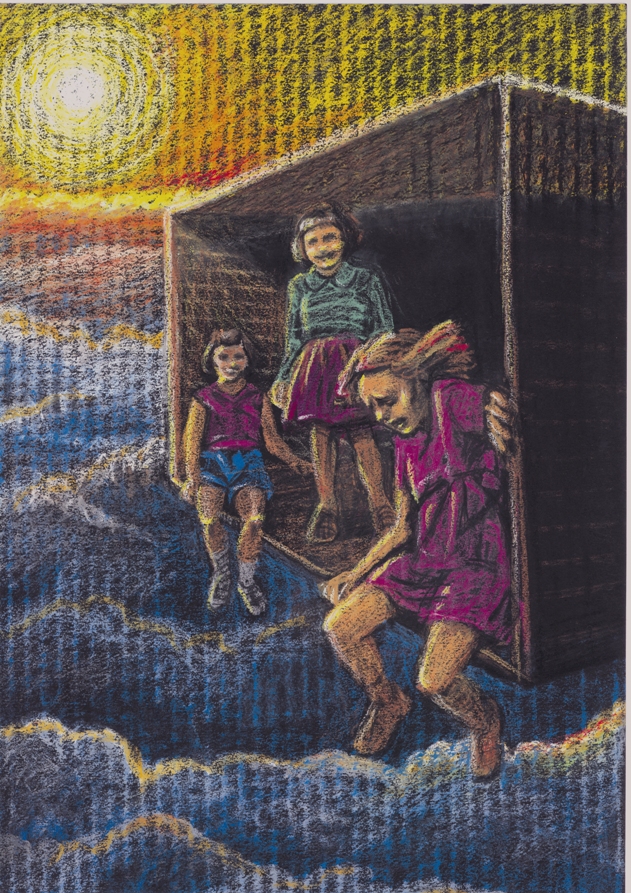

Slipping Away

Slipping awayThis is an illustration of a dream involving myself and two older sisters. I dreamed about my sisters as I remembered them, when we were children.

In the dream, we are in a small room, which is suspended high above the clouds. The room is much like a large cardboard box, the sort of thing we used to play with as children. My sisters were talking in a friendly and relaxed way. Even the one seated right on the edge of this room high in the sky was relaxed and smiling and not at all concerned about falling out. I, too, was right on the edge, but unlike my sister, I was terrified. I felt myself slipping off the edge and I was desperately trying to hang on. One of the most curious things about this situation was that neither sister was frightened, and neither sister seemed to relate to my panic. I wanted them to help – or to at least know of my predicament – but I was unable to communicate my distress. There was a strong wind that made it difficult to breathe or to speak. I also realised that from their perspective my distress was not apparent. My terror mounted as I felt myself slipping off and struggling to hold onto the sides of the room. A fall meant certain death. I awoke suddenly from the dream in a state of panic.

This dream represents my state of mind at that point in time, when I believed that death was imminent. In reality, these two sisters were at that time struggling with their diagnosis of breast cancer. Their relaxed state of being could be interpreted as either their acceptance of their situation, their being at peace with it, or alternatively, their being unaware of the potential danger. Another possible interpretation is that they appeared relaxed, because they were, in my view, safer than I was. Their cancers were primaries, whereas mine was considered to be secondary – which meant that it had already spread. So much so, that at the time of this dream, death was a distinct possibility and the dream a true reflection of my reaction. My two sisters’ inability to see the distress I was in is related to my inability – or perhaps unwillingness – to communicate my distress.

This is reminiscent of my childhood demeanour, when it seemed futile to communicate my difficulties. As a child, I sensed that in spite of our outward behaviour (which was very different), we sisters shared the same inner experience. We shared the same sense of anxiety, injury and hardship. Today, none of my aunts or other relatives in Malta has cancer. Yet, by the time of this dream, six women in my immediate family had been diagnosed with cancer – my mother, myself and four other sisters. None of my four living brothers had developed cancer. On reflection, the illness was not all we women had in common. Most significantly, we had all experienced much distress – primarily the result, I believe, of having been subject to the effects of war, displacement, loss of home and country, and the pernicious effects of the aggression within patriarchal cultures on women, that is, the belief systems and behaviours, which do not truly value our existence, nor honour, respect and nurture our essentially female natures.

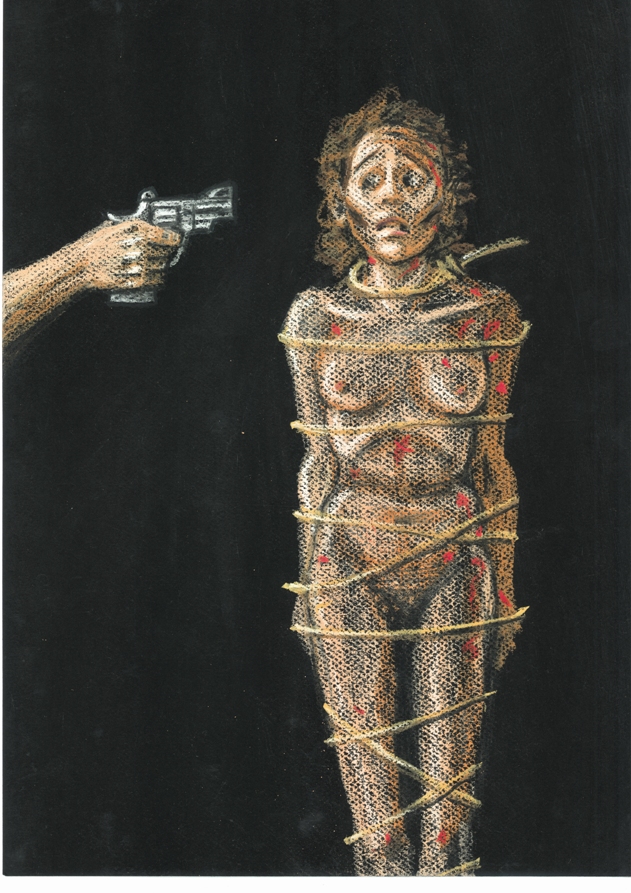

Living Horror

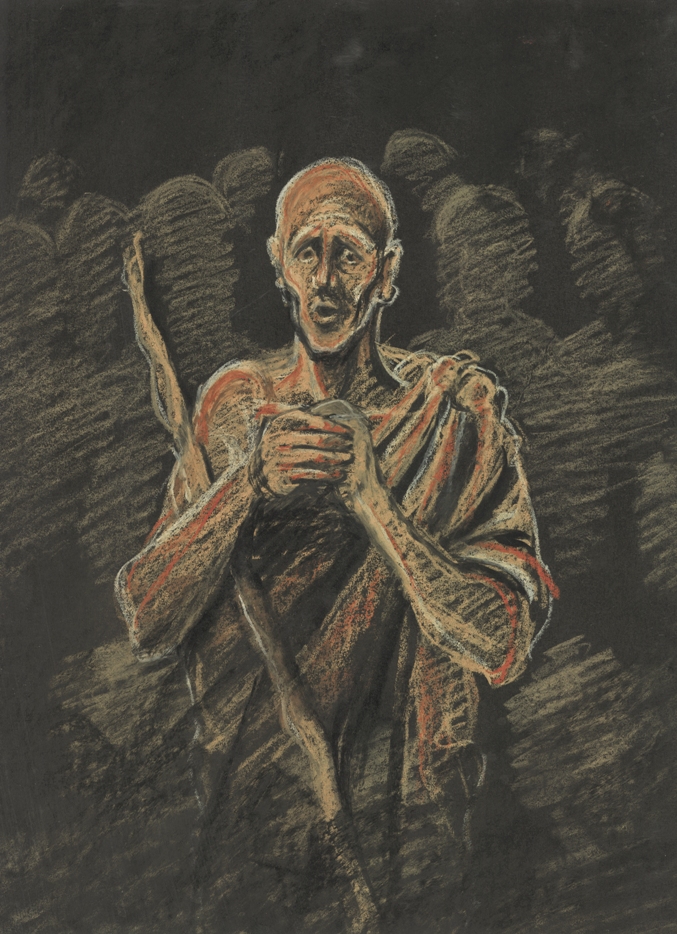

Living HorrorThis image comes to mind when I recall my demeanour, when I was critically ill and expecting to die. At that time, I was thin, and unable to eat. I was aware of the fact that I had metastatic cancer, that had now spread throughout my body (represented by the red spots in the drawing). The largest tumours – on my thigh, lower back and shoulder – created lumps, that could be seen and felt through my skin. The doctors’ efforts now seemed futile. There was no relief, no escaping this reality. In this image, the female figure represents me at this time. My demeanour is one of utter terror and horror. I am bound by rope to convey the paralysis I felt, and I was unable to move, unable to escape. Any movement at that time was excruciatingly painful, so I lay quite still. In spite of the morphine I was taking, I was conscious of my circumstances – that I was critically ill, that Western medicine was ineffective at this point, that I was about to die at any time, and in a horrible, dreadful manner. There had already been some close calls, and finally there would be the bullet that was aimed to kill. I would die the victim in life’s macabre game of Russian Roulette.

As I reflect on this illustration, I notice some features that reveal truths that were not drawn consciously. For instance, neither my hands nor feet are drawn. The omission of hands indicates to me the powerlessness I felt at the time; I felt unable to do anything at all about my situation. The omission of legs and feet describes my actual inability to move, to stand and to walk. I interpret the image of the gun pointing at my head as imminent and sure death. I also see it as a metaphor for the need to bring to an end my conditioned inclination to relate to my life and the world predominantly “from my head”, that is, from my thought-processes and intellect alone. There is no figure attached to the gun pointing at my head. In my mind, the figure is definitely masculine. It represents the aggressive, destructive and exploitative aspects of patriarchy.

This, for me, was ultimately a transformative and life enhancing event. I allowed myself to experience fully the feelings I had at the time – I was paralysed with fear, threatened with the real danger of losing my life, feeling extreme pain and futility. From this immersion, I noticed a sense of familiarity – I had experienced these feelings before. They were there in my childhood. I was shocked by my sudden discovery, that in spite of all my determined lifelong efforts, I had never truly transcended my childhood legacy. I had never really found the true peace of mind I had so longed for. My whole life had been one of struggle, full of effort to overcome my difficulties. At that point of realisation, I experienced profound and heart-felt compassion for myself, for the hardships I had endured, for the never-realised goal I had set for myself. I had believed wrongly that peace was something I would achieve in the future (after much hard work), however, as such, it remained in the future. This was a profound insight, one not understood merely by the intellect. It was an insight that I experienced with my whole being. I finally, profoundly, completely, understood.

This insight led to my consciously choosing a different way of being in the world. My previous focus on “doing” things (to overcome my difficulties) was clearly mistaken. My state of “being” was now paramount – a truth I had neglected unknowingly all my life, until then. Even during this very difficult and (seemingly) very late stage of my life when all seemed hopeless and futile, when I was racked with pain believing that I would not survive, I decided to live my life – however much longer it was to be – in the way I had always wanted to live it. I had believed previously that I had to struggle hard to overcome my difficulties, that I had to earn peace of mind and freedom from suffering. Everything in my culture seemed to support this delusion. I saw finally my life’s mistake clearly. I finally understood deeply – when I believed it was too late – an adage of profound wisdom and compassion: “There is no way to peace – peace is the way” (A.J. Muste).

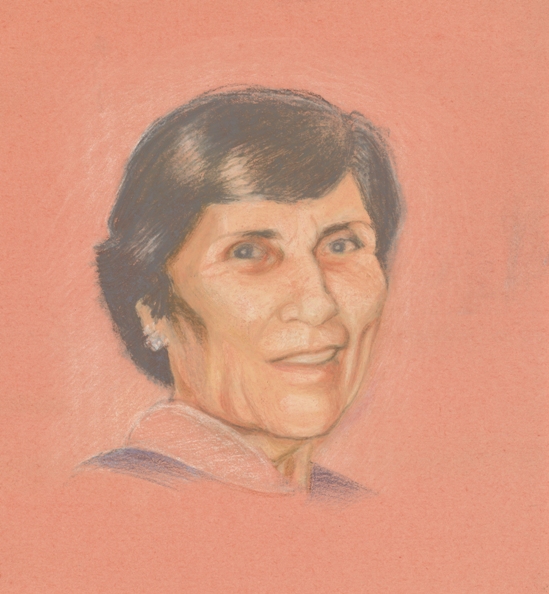

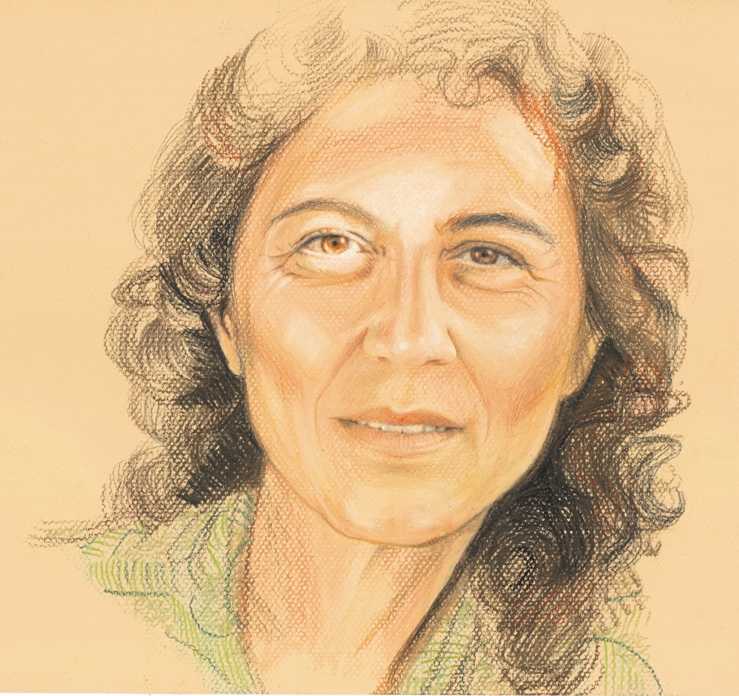

Mother

MotherThis is an image of my mother. When rendering this image, it was the very first time in this collection of illustrations that I did not reach automatically for a black coloured background, on which to draw. This image of my mother’s face is associated with light and warmth. This was one of the images that sometimes came to me after a series of nightmares, when I was critically ill. The effect was profoundly soothing and comforting. The disturbing effect of the previous dreams was diminished to virtual non-existence by my mother’s presence. Sometimes, her image was accompanied by a short dream involving my family of origin, and included happy events with my deceased sisters. When it came, this face was always the very last image in a series of dreams, as though it was intended to be so.

I associate this image with the very last time I saw my mother alive. She experienced a prolonged death in a nursing home. It was such a sad death, at the age of 80, after bearing thirteen children, leaving her own mother and sisters in Malta

to migrate to Australia, surviving uterine cancer, the deaths of two infant and two adult children, and finally, the death of her husband, my father. I was living in Perth at the time she was dying, and I came to Sydney for a week to see her. She died a day or so after my visit, when I left again for Perth. It seemed that she had been waiting to see me to say good-bye. I remember the very last look she gave me. She was very weak and unable to move or speak at the time. The look was of profound love.

As I gazed into her face, I understood her in a way I was not able to in my younger days. It was difficult for me to communicate with my mother when I was living with my family of origin. There was so much I did not understand. My questions were often not answered satisfactorily, so I stopped asking them. I became a reticent and withdrawn child. As far as I could, I found things out for myself, and worked out my own problems. My mother belonged to another time and to another culture. There was a mismatch between her Maltese culture and the new Australian culture, which I was meant to assimilate. I learned to speak English exclusively and to go to Australian schools. At school, I was put immediately in a kindergarten school class with other “foreigners”, not in Class 2A or 2B with my Australian contemporaries, but Class 2“O”, with other immigrant children. The effect was that I did not have a sense of true belonging to either the Maltese or to the Australian culture.

My otherness, my being different, was reinforced consistently. Even when my marks earned a place in the “A” class (within a year or so), I was still ostracised and called derogatory names by other children; I was still treated with hostility and suspicion. As I look back at the context in which this was happening, I remember that it was the time of the “White Australia Policy”. I have no doubt at all that such a racist policy contributed greatly to how I was perceived by my “true” Aussie classmates. I envied their sense of belongingness and safety. I envied, too, their apparent closeness to their mothers.

The tenderness on my mother’s face at the nursing home filled instantly the gaping holes in our relationship. The awkwardness of our past relationship dissolved completely in that one look. My difficulties and anxieties all seemed to disappear. So much so, that I was inspired to look within, to discover how to look upon myself in that deeply healing way, the way I always wanted and needed to be looked at (and treated) – with such kindness, such respect, and such love.

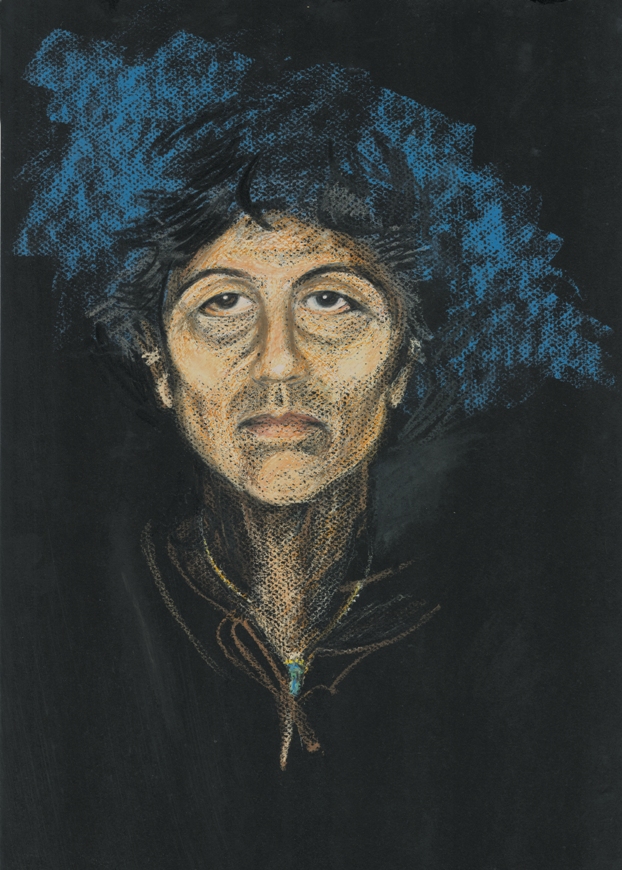

Morphine

MorphineThis self-portrait expresses my state of being, when I was on large dozes of morphine to counteract the pain from multiple malignant bone tumours. I remember vividly the overwhelming drowsiness and the constant, difficult struggle to stay awake. That was coupled by a certain longing for a peaceful and deep sleep, for oblivion, an escape from this brutal reality.

When morphine was first administered, I remember receiving it gratefully, as an act of mercy. At that point in time, every movement was painful, so much so, that I lay quite still. The subsequent side effects were endured necessarily: being startled awake by the inability to breathe; the deep, dark, sometimes suicidal depressions; daily panic attacks and nightmares; an inability to distinguish between wakefulness and dream states; severe constipation, and so on. The most dreadful consequence of being on morphine was my awareness of the long-term implications. The morphine was only palliative.

There was a dichotomy about my state of being during my illness. Though I looked physically weak, I was aware mentally of both my internal states and my surroundings. In fact, I was more sensitive than usual. I could perceive clearly acts of kindness. I was aware equally of acts of aversion and hostility. For example, I remember – with gratitude – the care I received from a particular doctor, when I was admitted into the emergency room of a public hospital, also the kindness of the doctors and nurses I encountered when I was then admitted into a local hospice. I suddenly felt safe. This was in sharp contrast to how I felt in response to the treatment I received at a private hospital just previously.

I had arrived at the private hospital to receive radiation treatment, which was delayed subsequently. During that night before the procedure, I became very ill at the hospital and I was unable to move, because of the pain. On request, the nurses helped Michael move me to the Accident and Emergency section immediately. The doctor on duty there refused to treat me, insisting that Michael pay the hospital fee of $2000, before he would do anything at all to help. The receptionist supported the doctor’s decision and refused my admission. Despite the attending nurse’s protests and expressions of concern, the doctor again refused to at least treat the pain. This was in the very early hours of the morning, a life-and-death situation, and they refused to act.

I am still stunned by the memory of this. Most of all, I am shocked that the doctor present at that time was somehow able to justify this unprofessional, insensitive and unethical behaviour. I may have been unable to move and respond, but I was aware painfully of what had happened. I remember what was said. Michael understood that his own response to this situation was to be based not so much on whether we could produce the money on demand, as to whether he was prepared to entrust this hospital’s staff with my health and well-being. Their highest concern seemed to be monetary. Panic set in, as he saw the hospital staff stand by idly, while my condition became increasingly critical. Michael decided quickly that he had to take me elsewhere. He asked the receptionist for the use of a phone to call an ambulance and the nearest public hospital. The receptionist asked for the money (for the cost of two phone calls) first. A skilled doctor at the public hospital I was then rushed to, diagnosed my condition as pneumonia and widespread bone cancer – probably the outcome of late stage breast cancer. He immediately, mercifully, gave me 60 milligrams of morphine for the pain.

This self-portrait shows a hint of a turquoise blue pendant, which one of my sisters gave me to wear. The pendant depicts an image of the Madonna and was said to contain miraculous water from Lourdes. While I instinctively understood my sister’s (and other people’s) need to inspire hope in me, at that time, it was very difficult for me to maintain any religious belief or faith. The pain and suffering were overwhelming and unrelenting. At the same time, I had a constant, urgent need to sleep. In terms of the conventional understanding of God, I felt a sense of complete and utter abandonment.

If a powerful, benevolent and healing force does exist in this universe, it became apparent in the kind and loving actions of those family members, friends and strangers, who did not turn away from me during this most painful and desolate time in my life. I remember the people, who visited from near and far, the unexpected gift of money to help pay my medical expenses, the home-cooked meals and boxes of fresh home-grown vegetables that arrived at the door-step, those who held my hand, those who held me in their hearts and in their prayers, and the warm, encouraging smiles on faces known and unknown to me. Some of these people, who offered their help and support during this time, had religious or professional affiliations, and some did not.

Michael was my most constant and dependable companion. To this day, I am in awe of his courage and loyalty. I can barely understand how he made the decision to stay, and how he kept making that decision – from one catastrophe to another, from one day to another, from month to month, and as it turned out, from year to year. It is hard to imagine how he was able to endure and to survive the ordeal, given his almost total isolation, and the length and seriousness of my illness, with its huge physical and emotional demands.

I can now understand how others can abandon their partners, family members and friends in similar circumstances. I believe it is essentially a matter of self-preservation. From my perspective, Michael and those who are able to stay in the midst of “the molten chaos” and the “living grief” of a beloved’s dying, do so from a place of selflessness, one of unconditional love and compassion.

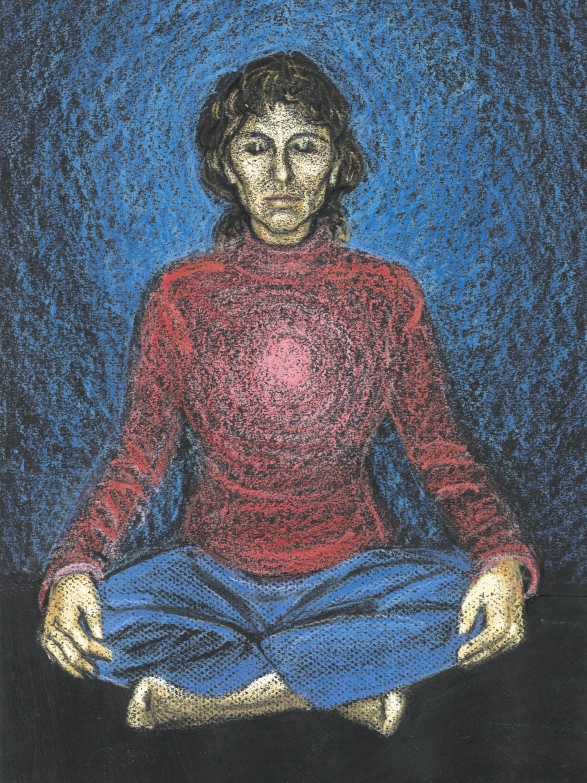

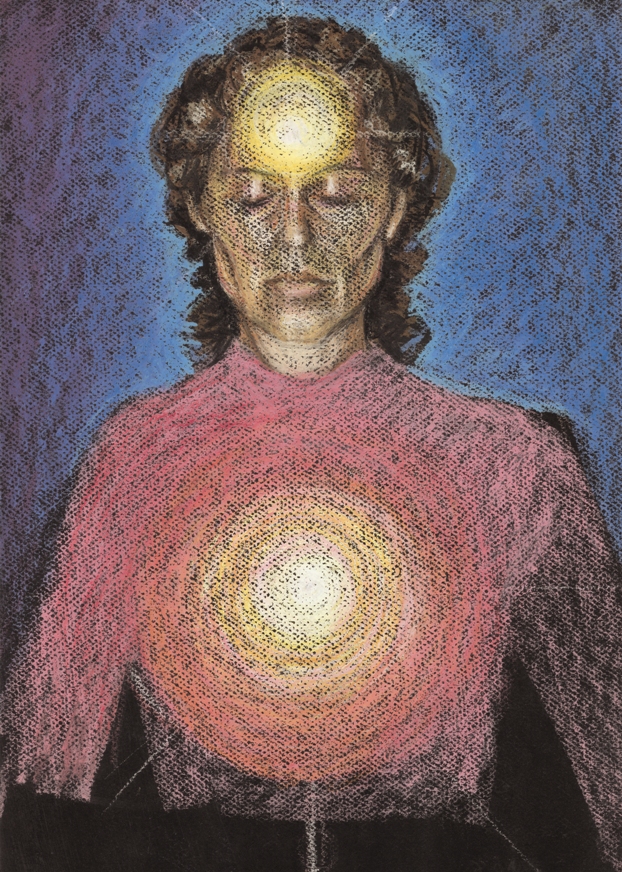

Heart of Peace

(two images)

Heart of PeaceDuring my hospitalisation and afterwards when I came home, I found it difficult to sit formally in meditation. For one thing, I was unable physically to assume the posture. Even when I was finally able physically to sit in meditation, the level of morphine I was taking meant that I would inevitably fall asleep, consistently, every single time. At first, I fought the inclination, then I realised it was futile. I clearly needed to rest.

Instead, I assumed a posture in my mind, a mental attitude I adopted to cultivate the feeling of peacefulness within. This was extremely important to me, because my life had become the lived experience of horror, pain, exhaustion, of grief and utter misery. I needed to counteract this overwhelming aspect of my reality with a practice that enabled me to transcend my physical and psychological reality. At any given time, I would close my eyes and breathe in health and well-being, and breathe out weariness, distress and disease. My attention turned inward toward my heart chakra (energy field), and I focused on radiating a feeling of loving kindness towards my physical body.

In the first illustration, the radiation of loving kindness is depicted in pink, a colour associated with unconditional love. The colours of the clothes I am wearing in the illustration are colours I wear normally at home. The clothes suggest the need for protection and safety. I chose a deep velvety blue for the colour around my head. It was the first ball of colour I saw when I first began to see auras, perhaps the colour I most resonated with at the time. The blue was dark and a beautiful, soft, luminous colour.

In the second illustration, both heart and head are illuminated. I learned from the insight into my need for true peace, that the concept “peace of mind” is an inadequate one. The concept “peace of mind” maintains effectively a separation between mind and body. My previous efforts to create and develop peace of mind, ignored the needs and feelings within the body. On reflection, I believe a major cause of my illness was that emotional distress was being dealt with on a physiological, rather than on a psychological level. I now view the state of peace as both physiological as well as psychological. The feeling depicted in both illustrations is one of stillness and centredness. It is a core of peace in the eye of the storm.

Living in the ShadowsSome time ago, the facilitator of a local cancer support group phoned me at home. She asked me to visit a young woman (aged 41), who lived in my neighbourhood and was critically ill. This young woman had refused an invitation to attend the local support group, because she felt uncomfortable about attending a group with women much older than herself. I was the youngest of the group (53), thus closer to her age. The facilitator believed that my experience of surviving a critical illness might encourage her.

Though I agreed to visit this young woman, I noticed my resistance, which was a certain reluctance. It may have taken two weeks before I finally rang the bell at her front door. An athletic young man with a shaven head answered, and there was wariness and distrust in his demeanour. I recalled seeing him on a number of occasions, walking the streets with a wooden staff in one hand and the collar of a large German Shepherd in the other. I introduced myself and explained why I had come. There was a voice and the sound of movement coming from the adjacent room. Only then, I was ushered in.

From the shadows came a voice, then finally the figure of a frail young woman. She was thin, emaciated. She wore a scarf over her (hairless) head. She could barely speak. Her lips were peeling. She explained that she was undergoing chemotherapy and had an ulcerated mouth. There were also growths in her neck that prevented her from swallowing food. She was quiet and still. I sensed her dark mood, her deep depression.

I addressed her automatically by the name I had been given, “Stacey”, but I noticed that the young man, Salvidor, called her by a different name. After a time, Salvidor left and Stacey made some tea. Her home environment was immaculate. It was a small wooden cottage surrounded by neatly clipped trees and a garden. The side veranda had a sitting area, which overlooked a gully hidden by wilderness.

Stacey told me that she was adopted as a child, and that her new mother gave her a different name. She had a twin brother, from whom she was separated long ago; they were each given to different families after the death of their natural mother. Stacey spoke of a traumatic childhood, of a very difficult relationship with her new parents. She was convinced that her adoptive parents knew the whereabouts of her twin brother, but they resolutely withheld the information from her – even now. She longed to see him again. Salvidor called her “Brianna”, the name her natural mother had given her. She preferred to be called by that name. It was the one link she still had with her real mother.

Brianna also spoke of her illness. After receiving her test results, she asked her oncologist for his opinion, to “give it to her straight”. She said that he told her: “You are going to die”. Her mother was there last night, telling her the same thing, over and over: “You are going to die”. She also criticised Brianna – loudly – for her involvement with Salvidor; she judged the relationship as sinful. I now understood why Brianna was so despondent.

Brianna then spoke about Salvidor. She had only recently met him. He had moved into a unit next door and they developed a friendship. Salvidor was health conscious; his physique was slim and muscular. He brought her herbs and foods, that he believed would build her strength and give her energy. In spite of his attention, Brianna felt cautious about becoming involved with him. She explained that her (second) husband left her last Christmas. He abandoned her when she became very ill. She was worried that this new relationship was developing too fast, too soon after the separation.

There was much pain in what Brianna said. The only time her facial expression eased was when she mentioned Salvidor. The break-up with her previous partner had evidently been painful; that relationship was over. I could understand her attraction to Salvidor. He seemed to be the only person in her life, who was giving her any measure of companionship and comfort.

Brianna became relaxed increasingly and peaceful in our two hours together. I left realising that this could not be a one-off visit. Brianna needed ongoing support. I now understood my initial reluctance to make this visit: I was feeling drained of energy, absolutely exhausted.

Immediately on my return home, the phone rang. It was my friend Mellie, and there was urgency in her voice. She wanted my advice on how to relate to her friend, Caroline, who was just given the devastating news that she had widespread cancer. Caroline was in her early 50’s. She was a shiatsu practitioner, and I remembered Mellie speaking very highly of her skills. The hospital staff had apparently awakened Caroline during the previous night to tell her the news of her condition, also to urge her to begin chemotherapy as soon as possible. Caroline was in a quandary; she did not know what to do. Mellie was on her way to the hospital to see her, and she was clearly in a state of panic.

I told Mellie that I was just about to have a rest and that I would talk to her at length later on. For now, I wanted to express a couple of thoughts that had come immediately to mind. I suggested that if Caroline wanted to discuss whether to undertake chemotherapy treatments, it was important that she made an informed decision, one based on all the best information available. For instance, did Caroline understand clearly why she was being recommended this treatment? What were the medical staff hoping to achieve, and at what cost (to Caroline’s body, mind and spirit)? How had others with a similar condition fared with this treatment? Was Caroline aware of other options? Did she need more time to make a decision? I then addressed the issue of how Mellie might relate to Caroline. I counselled Mellie against asking Caroline how she was feeling (it was evident). I suggested that she might simply be present for Caroline as a friend, to listen deeply to her and to respond to her concerns appropriately. Caroline was more likely to make the right decision for herself in a clear state of mind, rather than in a state of shock and panic. Mellie seemed satisfied with this response and hung up. I then went straight to bed.

Around this period of time, my brother and a friend also contacted me about helping people they knew who had medically incurable illnesses. I began to feel uneasy increasingly about this new role, that was being thrust upon me. My inclination was to decline these requests. I felt intuitively a disinclination to become involved. Counselling someone with a brain tumour, who was given months to live, for instance, needed time and care; it was clearly not going to be a short, single conversation. Moreover, it was painful vicariously for me at that time, to be reminded of the ordeal I had just experienced recently.

After much consideration, I decided to refer such inquiries elsewhere. I realised I was slipping back into my old role as a counsellor, one that I was trained for, but no longer wished to pursue – at least, not at this time. Other people, like Petrea King and Ian Gawler, had written books about overcoming medically incurable illnesses, and held groups and retreats on an ongoing basis; I would refer people to them. I felt the need to focus on myself, on my own health and well-being. So, I wrote Brianna a letter explaining that I could not see her on an ongoing basis. I wanted her to know about a local group, whose members were trained in palliative support care; I would introduce her to a group member I knew, whose presence was uplifting and in a similar age group. I also phoned the cancer support group facilitator and told her that she was asking too much of me at this point in time. My contact with Brianna could not be on a single-visit basis; she needed someone who was able to “hold” her in the sense of being able to give her ongoing support.

Nevertheless, Michael and I went to Brianna’s home. I really expected she would be too ill to receive visitors, but I did actually talk to her. She and Salvidor were about to leave to attend an auction, at which Salvidor hoped to sell his motorbike – he wanted money to pay for a trip they were going to take. Salvidor knew of a retreat centre in Melbourne, which was run by a renowned practitioner of Traditional Chinese Medicine; he was convinced that Brianna would find help there. Brianna wanted to sell her car to pay for the trip, but Salvidor insisted on selling his motorbike. He knew that Brianna needed her car; it was her only means of transport.

Brianna showed me her neck. There was an area above her left collar bone that was swollen massively. The distraught look in her eyes confirmed my suspicion that this was a tumour. I asked Brianna when she had first noticed it. She said that it appeared during an argument with her former husband, just recently. There seemed to be a message in this. I suggested that it might be related to her anger, that she may be able to heal it with the antidote, the opposite emotion. “Send it love. Give yourself love,” I said.

I managed to slip her my letter of withdrawal, but I also promised to see her again later that day. I remember Michael asking her if there was anything she needed. “Life,” she said. Brianna phoned me later that day when she returned from the auction; she wanted to cancel our appointment. I realised from her tone of voice, that I had made a terrible mistake. I needed to make amends, urgently.

I went to see her the next morning and stayed a while. I apologised for my insensitivity; I would see her when I could. I then gave her a copy of Petrea King’s book entitled “Quest for Life”. We then talked about her upcoming trip. Brianna was feeling somewhat apprehensive about it. At the same time, she sensed that this was her only hope, and she felt encouraged by Salvidor’s unwavering support and optimism. Later, I introduced her to Pat, a member of a palliative care support group in our town.

Brianna and Salvidor visited me at home just before they went to Melbourne. They left me with a basket of fruit and vegetables, and asked me to look after their mail while they were away.

About seven weeks later, I noticed Brianna’s car in the carport – she and Salvidor were back. Brianna was looking radiant. It was a total transformation. She told me happily that she was feeling much better. She showed me the lump on her neck; it had remarkably reduced in size. She said that she could now walk up the steep hill behind her property and down to the river with Salvidor. She had barely been able to walk around her house and yard before she left for Melbourne. While she was at the retreat centre, she had adopted a complete lifestyle and attitudinal change. She had started meditating and doing Qigong exercises for hours every day. She was following a prescribed diet and using Chinese herbal supplements. She was full of energy and optimism. I discovered that she wanted to have a baby, and subsequently became pregnant, with twins.

I saw her once more. Then, I received a phone call from Salvidor one Friday morning. He said that Brianna maintained her well-being until her ex-husband and family members went to her home. They treated her as if she was dying and came to stake their claim on her property. Their ensuing arguments and negativity extracted a heavy toll on Brianna. Her health began to decline rapidly. Salvidor had phoned to let me know that she had been taken to her parent’s house, then to a hospice. She had reverted to the name she was commonly known by, “Stacey”. She was refusing visitors.

This news was so unexpected and so tragic, that I was overwhelmed with grief. My first thought was to send her flowers with a card, which included my telephone number. The news was also confusing. Why had she left Salvidor? Did Stacey go willingly to her parent’s house (given her family history of trauma and abuse)? The florist phoned me late in the afternoon to say that Stacey was no longer at the hospice. She had been transferred to her parents’ home. The florist offered graciously to take the flowers there on the following morning.

After the weekend, I phoned her parents’ home, realising the need to use tact and diplomacy. Her mother acknowledged receipt of the flowers and explained that although Stacey told her that she wanted to phone me, she did not have my number. In any case, Stacey was on high doses of morphine and was generally too weak to make the call. I thanked Stacey’s mother for the information, left her my telephone number, and asked her to let Stacey know that I had phoned.

On Wednesday morning, I went to the local hospital to talk to a community nurse, who I knew well and trusted. At this stage I had not received a phone call from Stacey or her parents. I was unsure how to proceed with this situation, and had some doubts as to whether to persist. The community nurse told me that she was bound by patient confidentiality, so she was limited in what she could say. She admitted to also being concerned about Stacey, because Stacey had refused all help – even palliative care from the community nurses. The community nurse recommended that I persist in my efforts to contact Stacey, because I may be the only person she would see.

Salvidor later phoned me at home, to tell me that Stacey had been taken to the local hospital. He had tried to see her there, but was refused entry by her parents. Nevertheless, he forced his way in. He managed to see Stacey and to exchange a few words. He now wanted me to ask her a question on his behalf: did she want to see him again? Before I had a chance to ask him why she was refusing to see him, he confessed that he had argued with her when they were last together. He said that tensions had been building up. He was feeling stressed about Stacey’s illness and around her relatives, particularly at the point when he could see that she was again beginning to deteriorate. She had miscarried very early in her pregnancy, and had begun to lose all hope. He confessed to losing his temper when her family were there, and handling her roughly. He had called the police during one of these heated arguments with her family. The police interviewed him subsequently, and Brianna had been taken to her parent’s place. He was ashamed and very sorry. He realised after this incident that he needed help with his anger, and promised to actively pursue counselling when he relocated. He was planning to return to his homeland to care for his ageing mother.

I went to see Stacey that same afternoon after a nap. The nurse on duty greeted me warmly – he remembered me from my own hospital admission. I asked to see Stacey. He told me to wait while he checked on her first. He came back soon afterwards and ushered me in to her room. Stacey’s father was outside the room, her mother was sitting against the wall at the foot of the bed. I came in and introduced myself. Her mother greeted me in a friendly manner; she asked me to call her by her first name. She withdrew considerately from the room, so that I could have a private word with Stacey.

I looked carefully at Stacey’s small skeletal figure propped up in the bed with pillows. Her head had dropped to one side; she was unconscious, frowning, and breathing heavily. There were two quite prominent lumps on her body above the blanket on areas not covered by her nightie; one was located on the right side of her chest, the other on the left side of her neck. Her (dark) hair had started to grow again. When she woke up, she indicated that I bring a chair close to her bedside. I then took her hand gently in mine, and while stroking it lightly, smiled at her. It struck me suddenly how very much easier it was to be on my side of this dynamic.

Stacey could only utter a few words at a time. She said that she was “too sick”, and it would “not be long now”. She also said that she was not going to be able to hurt anyone anymore. I responded by saying that she had brought a lot of love and joy to Salvidor’s life. She looked askance at me with her misty eyes. Yes, I said, I knew that to be true, because he had told me so. Stacey said that she had told Salvidor to let her go; he was young, he would find someone else. I nodded slowly, I knew then that Stacey had decided to move on. I realised sadly that she now had little to live for; life would be extremely difficult, at least in the short term, and she did not appear to have the loving support and understanding she needed to come through this ordeal. She seemed to be closing doors, preparing to die.

Brianna died on the following Sunday morning. She had asked to be taken to her own home, but was unable to manage without intensive care. She was then taken back to the local hospital, where she died soon afterwards. I heard subsequently that there had been a small memorial service held at her grave site; attendance was restricted to a just a few family members. Caroline also died. Her children had urged her to undertake chemotherapy, because they believed it was her only hope.

Cancer (Mis)informationIn my neighbourhood there is a small, organised and well-trained group of locals, who support people receiving palliative care in their homes. The last time I saw this group together was some time ago, when they invited me to talk to them about my experience of critical illness. Members of this group visited me when I was very ill; they also provided Michael with (much needed) respite care. One of them, Hannah, has since become a friend.

Just a few weeks ago, Hannah invited me to accompany her to an information morning that was hosted by the palliative care support group. She said that a representative from a cancer lobby group was giving a free public presentation on cancer and the prevention of cancer. My immediate reaction to Hannah’s invitation was negative. I was familiar with this lobby group’s perspective and found it dogmatic and strongly biased. Nevertheless, Hannah persuaded me to go.

The presentation itself was well delivered, but I became increasingly irritated by the inaccuracy of the information being presented. There were at least two others in the room, who shared my disquiet with the quality of the material. Those who dared to, spoke up – myself included. Still, our questions and objections were not addressed satisfactorily. It soon became apparent that any further debate was futile.

I arrived back home feeling frustrated, and Michael suggested that I express my feelings in writing. He further suggested that I send a letter with my feedback of the information session to the lobby group’s head office in Sydney.

Michael’s suggestion appealed to me. This represented an opportunity not only for emotional catharsis, but also for speaking on behalf of cancer sufferers themselves. This organisation could make a difference to the treatments cancer sufferers receive, and to the attitude of those with whom they interact. I remembered, vividly, how unskilfully Brianna and Caroline had been treated by those closest to them, and how isolated emotionally they had become during their dying – a time when they most needed help and support.The following is a copy of the letter I then wrote (names withheld):

To Whom It May Concern:I have just attended a cancer information morning hosted by a group that provides palliative care support for local residents. The presentation was given by (one of your organisation’s representatives). This letter is my response to this presentation.

I will begin with some personal details so as to provide a context, from which this critique is given. In academic terms, I am a PhD candidate with the School of Health and Human Sciences at Southern Cross University, Lismore – in the Northern Rivers district. I am currently writing a PhD thesis on the experience of dying (from cancer). I have a Bachelor of Arts degree in Behavioural Studies (1989), and a Master of Arts degree in Art Therapy (1999). Professionally, I have worked for a number of years as a counsellor, consultant, and family therapist with individuals on an outreach basis and within agency settings. I have facilitated therapeutic group programs and co-ordinated the therapeutic group work activities of a large organisation. I have also worked extensively as a counsellor and support worker in a voluntary community service capacity in a variety of areas, including hospice support work.

In addition to this, I have significant experience of cancer. Six of my immediate family members have been diagnosed with cancer from which two of my sisters have died. I have personally suffered Stage IV cancer, including widespread metastatic bone cancer – the result of late stage breast disease. I have, for many years, dealt with members of the medical profession and with complementary and alternative therapists.

This morning’s presentation was professional in the way it was delivered, so the issues I raise here are not about the presenter. My concern is that the findings of the research that I am doing for my PhD are at variance with the information presented. Please consider the following observations:

Treatment recommendations were quoted to be “evidence-based”, and I know from personal experience and from my literature review that although the treatments recommended for cancer may be “best practice” treatments, they are not necessarily evidence-based. “Best practice” merely indicates that a particular treatment has frequently been used for a particular condition, not that the treatment is being recommended based on evidence that it is the most effective option available.

The important role of complementary and alternative therapies is not accurately presented in (your organisation’s) literature nor, consequently, in the information session this morning. While it is true that Biomedicine is effective in detecting and treating some forms of cancer, it is equally true that some other forms of cancers do not respond to medical treatment. Some forms of cancer are considered untreatable and medically incurable. And yet, people do survive them. Biomedicine is not a holistic approach; it is one of many strategies available to cancer sufferers. (The information you are disseminating) seems to be treating Biomedicine as the only realistic treatment option for all cancers. This is ethically unsound.

Mention was made of the placebo effect. The placebo effect has been found to work in the opposite direction. It is called the nocebo response – “I shall harm” (Walter Kennedy, 1961). If the expectation is expressed that a person is not going to heal, that can equally prove to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

When biomedical practitioners find they cannot cure or treat a particular form of cancer, they often respond by giving what amounts to a death sentence. A more truthful response would be for practitioners to openly declare that Biomedicine is not holistic and does not have all the answers, and that while Biomedicine may not at this stage be able to treat a particular form of cancer, hope may lie elsewhere – because some cancer sufferers do survive the most aggressive and medically untreatable forms of cancer.

I am not suggesting that a person should be given false hope. I do strongly advocate that all hope is not taken away. Cancer sufferers must be given wide ranging information that will provide them with an opportunity to look into other perhaps less conventional treatments, that may well provide help, even cure.

Individuals must be allowed to take personal responsibility for their treatment. They must be allowed to choose the best treatment options. The best decisions are made when all options are communicated, and made available. This means that options other than medical treatments alone should be investigated and made known.

More information on the environmental and lifestyle factors that cause cancer, xenoestrogens, and on breast cancer specifically is needed because it is the leading cause of death in women, particularly in the 45-64 year old age group(www.breastcancerfund.org).

I know from my research that many clinical trials related to treatments for cancer are funded by pharmaceutical companies. Pharmaceutical biotechnology is a multi-billion dollar industry world-wide. There is a vested interest in pharmaceutical companies to find (only) drug-related treatments for cancer.

A question was asked during this morning’s information session about the type of trials being funded by (your organisation). Trials funded by drug companies are essentially biased. The concern is that (your organisation) may be reflecting this bias. I emphasise the fact – there are other effective approaches that should be examined without bias.

I suggest, for instance, that a research project might be conducted on those who have survived medically incurable forms of cancer. Their personal qualities and the methods of treatment they chose should be examined. The results of such a project could inspire hope and give direction to the many people whose cancers cannot be medically treated and cured.

These are just a few of the comments I feel compelled to make after listening to the information session this morning. Cancer is the leading underlying cause of death in Australia today, and the incidence of cancer is rising (ABS, 2006). The quality and accuracy of information on cancer is vitally important to everyone. The most beneficial outcome is that suffering will be averted, or at least ameliorated. For individuals who are facing the horrific and agonising experience of cancer, treatment decisions must be based on (all) the best information available. Treatment decisions make the difference between life and death, also between the quality of life and the quality of death.

Thank you for your attention,

Carmen Zammit B.A. (Behavioural Studies), M.A. (Art Therapy)

30th October 2006__________________________________________________________________________________________

Since writing this letter, I received an acknowledgement of receipt of my letter, with an assurance of a fuller response after their representative was consulted. However, the promised response never came.

How should I interpret this failure to reply? This was an organisation, which relies on financial support from the Government and from the general public, it is one, which I believe must, therefore, take responsibility and account for its actions. I had a reasonable expectation that I would receive a response characteristic of or befitting the profession which this organisation represents. The latest report shows that many of the Board Members are primarily from the medical profession. Considering the lives at stake, the extreme suffering involved, and the financial and emotional cost to the community, the response to cancer should be a thorough and concerted one. I, for one, would like to see responses to cancer, that are patient-centred and free from self-interest, bias and deception.

Withdrawing / Emerging

Withdrawing / EmergingThis portrait depicts my state of health at the time of this writing. It is now four and a half years after my initial diagnosis of metastatic cancer, and approximately two and a half years since my admission into the hospice I was not expected to leave. This image reflects my present state of being. Amazingly, I am alert and well. I have regained my health and mobility. I have taken myself off all the medication I was prescribed – a process that had taken courage and faith, and two years altogether to complete. The withdrawal process began when I first intuited that I was recovering. Until that time, I was reliant totally on my medication, which gave me a significant measure of pain relief and control of other symptoms.

When I was in the hospice and for some months afterwards, I was confined mostly to my bed, on which I lay quite still. My wanting to return home from the hospice was seen as an opportunity to grant my last request. I was told by my doctor in response to my inquiries that I could expect that my levels of medication would continue to increase until my death. However, contrary to all expectations, I very gradually became able to sit up independently, and then for increasingly longer periods of time. On discovering this hint of improvement in my health, I decided to begin to withdraw my medications, initially from the anxiety and sleeping tablets, then incrementally all the others. At that time, the medications I was taking included: morphine tablets (MS Contin for pain), a morphine liquid mixture (Ordine for “breakthrough” pain), paracetamol (Panamax for pain), docusate sodium and senna (Coloxyl with Senna laxative), Macrogol 3350 (Movicol sachet laxatives), metoxlopramide tablets (Pramin for nausea), omeprazole (Lozec Acimax to reduce acid secretion in the stomach), Temazepam (to assist with sleep), Diazepam (to assist with anxiety), chlorpromazine (Largactyl, a major tranquilliser and neuroplegic), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (Celepram anti-depressant) and a bisphosphonate (zoledronic acid, Zometa). I withdrew from the minor drugs as soon as I felt I could, and I withdrew from the major drugs one at a time.

For example, I withdrew from 100 milligrams of morphine, morning and night, at an average rate of 10 milligrams per month. On two occasions, I needed to go back on to my previous dosage. On reflection, these were times of added stress. I became aware gradually of the fact that environmentally induced stress had a profoundly negative effect on me. I believe that this was because I was already dealing with an enormous amount of distress from being critically ill. Even those situations that were anticipated as pleasurable were sometimes experienced as stressful, as for example, when family or friends stayed over. My daily need for peace and quiet had become extremely important to me, and major disruptions to my routine affected me negatively. Over time, I learned to become aware of my physical and emotional needs and limitations, and to avoid or minimise any form of stress. When I perceived any physical or emotional distress, I would then wait until I had regained peace of mind and body, before continuing with my withdrawal process.

In terms of the morphine, I had the advantage of knowing that withdrawing from opiates is a physically painful process. I had worked as a drug addiction counsellor for some years and I had learned this from my heroin-dependent clients. When I consequently felt the pain of withdrawal, I knew it was to be expected. The challenge for me was to discern whether it was, in fact, the pain from malignant tumours. I judged this by noting the location of the pain. I reasoned that if it was tumour pain, it would be felt in those places I knew the tumours to be, especially the largest of them. I found this not to be the case, and so I felt the confidence to proceed.

It took about a year to withdraw totally from the morphine, then I began withdrawing from the anti-depressant, and so on, until I finally discontinued the last drug, Zometa, which was administered intravenously on a monthly basis. In medical terms, Zometa is a bisphosphonate, an anti-resorptive agent used in the treatment of metabolic bone diseases – such as in my case, tumour-associated hypercalcaemia. My understanding of this terminology is that this drug stops the tumours from leaching calcium from the bones into the blood stream (which is a toxic condition, fatal if left unattended); this drug also stops the bones from regenerating, and thus inhibits the further growth of malignant tumours in the bone. Like morphine, the bisphosphonate was not curative, it was only palliative. My withdrawal from the drugs in general was a slow and gradual process. The outcome – unknown to me at the start – was to be my total and successful withdrawal from all the medication.

The withdrawal process was a self-managed process, guided largely by my intuition. This was not the first time I had acted on insights about my health, and I had learned from painful experience not to ignore them. For me, following my intuition about my health was about obeying messages from my body. I had the distinct impression that I was getting better, in spite of my medical prognosis. When I first felt the inclination to withdraw from the medication, I encountered opposition from my doctors and nurses. I remember their expressions of surprise and puzzlement when I made decisions that did not conform to what they believed was true about my state of health. I was actually accused of being “in denial” by those people, who were convinced that I was doomed. I sensed that they truly believed in my “terminal” status, the hopelessness of my condition, and the efficacy of the drugs I was taking. Nevertheless, I was determined to proceed.